Replacing Slack, Part 2: The Three Waves of Challengers

Looking at Slack's rise and 10 years of competition

Over the years, many great teams have taken on to challenge Slack.

I’ve come across around a dozen companies in the space, and many more have undoubtedly slipped under my radar1.

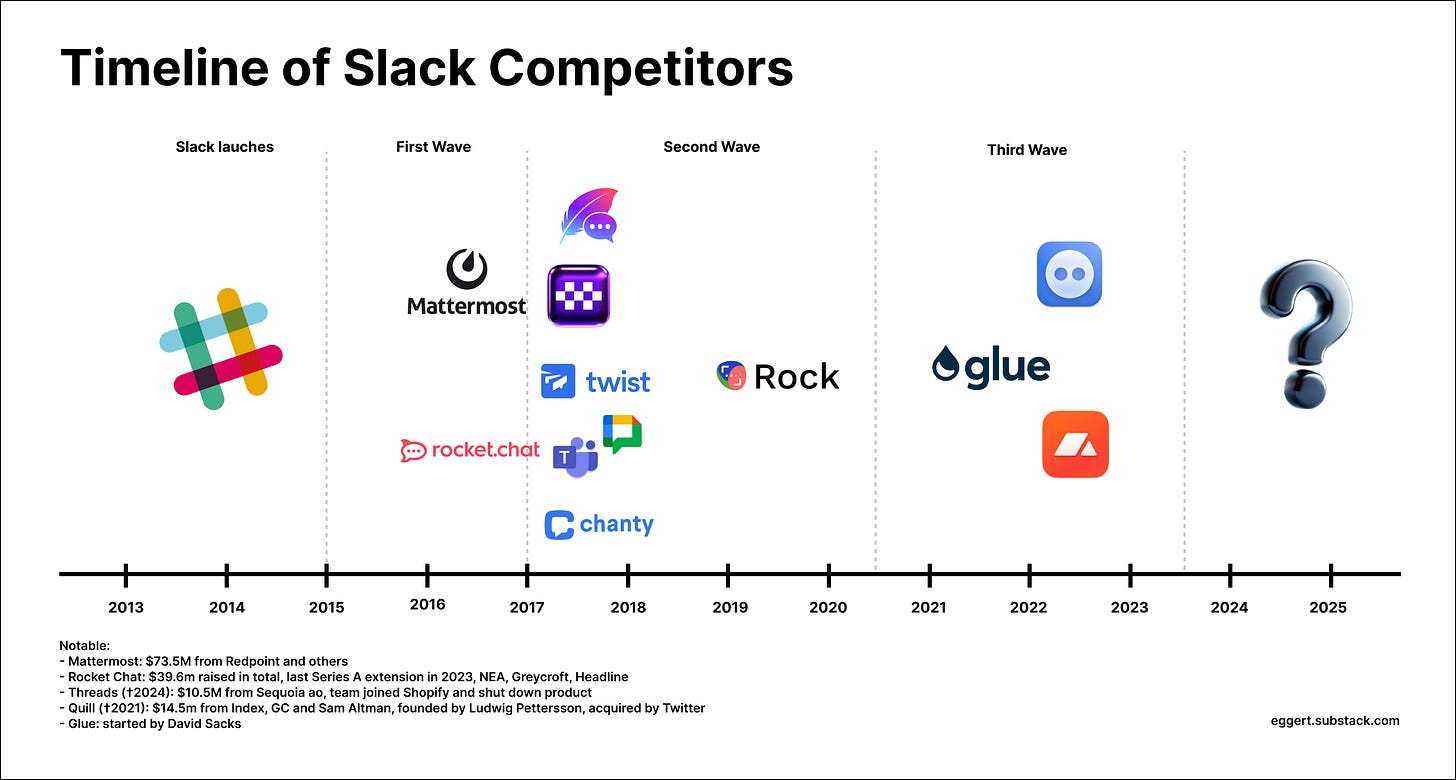

Slack’s challengers can be clustered into three distinct waves:

the early direct competitors that emerged around 2016 as Slack’s popularity soared,

a second wave of differentiated competitors that appeared later as Slack’s weaknesses [cf. part 1 of this post] became apparent, and

a recent third wave of next-gen challengers attempting to redefine the space. Looming over these waves is the elephant in the room (Microsoft Teams) along with other ‘me-too’ products from tech giants like Google and Zoom.

Much has already been written about its phenomenal rise, fueled by Microsoft’s distribution power and bundling strategy. Microsoft Teams deserves its own deep dive, but that’s not the focus of today’s discussion for three reasons.

First, much of Teams’ growth likely came not from companies abandoning Slack but from Microsoft capturing a different segment of organizations (tech laggards), especially during COVID-19.

Secondly, there’s also (both reportedly and anecdotally) a stark contrast in how Slack and Teams are used in comparison. While Slack has a high engagement as workplace chat, Teams is primarily viewed as a video conferencing tool alongside email as a core communication channel.

Finally, Microsoft's strategy is creating a "default + good enough" product. Through bundling and cross-selling, Microsoft was able to leverage its existing enterprise distribution and effectively give away chat for free. This is not my lens in the context of this post, even though it’s proven to be a perfect strategy for Microsoft. My main interest is why we don’t have a better Slack.

One Hacker News user’s satirical take might hit close to the truth:

Slack is so easy and fun to use that we use it for things we shouldn't be (fun channels, fun integrations). It creates too much noise and hard to extract signal. It ends up being distracting past 100+ people company.

Teams is so bad that people try not to use it. It forces you to use it minimally because everything is terrible. It actually ends up being more productive than Slack.

Despite the efforts of numerous capable teams backed by top-tier investors, few Slack challengers have gained significant traction. A growing amount of these companies seized their services (usually in acquihires), leaving Slack’s dominance largely unchallenged.

Most have centered their strategies around solving Slack’s notorious noise problem. Others have ventured further, integrating task management into the communication flow — an area Slack itself has been exploring for some time. No one has found overwhelming success, with the notable exception of going into heavily regulated areas with a security-first positioning.

So why hasn’t anyone succeeded in replacing Slack?

First and foremost, Slack is incredibly sticky. Users have grown familiar with it, and many have multiple Slack workspaces outside their primary work. This creates a significant barrier to switching. Moreover, shared Slack Connect channels and a high amount of installed integrations make switching to a different platform even more difficult.

For a new challenger to succeed, it may require starting with a clean slate, targeting newly founded companies that haven’t yet committed to Slack. However, gaining the necessary attention and trust to convince these startups of a clearly superior solution remains a significant hurdle.

For some time, it looked like building adjacent solutions could be a better strategy. Companies such as Tandem saw some initial traction by addressing specific gaps. However, even these promising attempts have ultimately fallen short, failing to break through Slack’s entrenched position in the market.

How did Slack manage to carve out this position for themselves in the first place?

From Launch to Acquisition: The Rise of Slack

Slack’s journey began as an internal tool for Tiny Speck, a company co-founded by Stewart Butterfield, Eric Costello, Cal Henderson, and Serguei Mourachov, initially focused on a now-defunct online game called “Glitch.” When the game didn’t take off, the team pivoted, launching Slack publicly in February 2014.

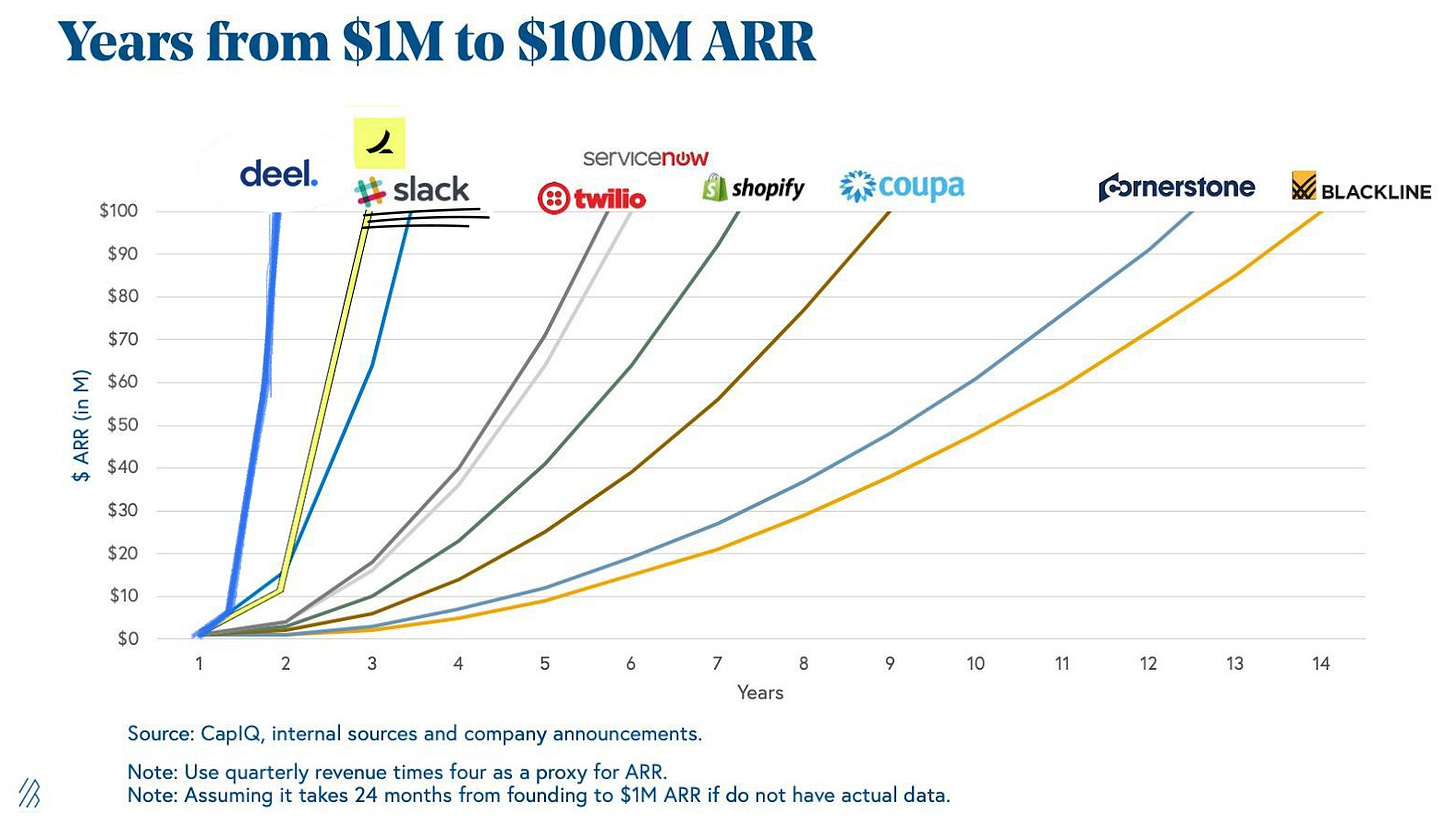

Despite not being the first in its category (Hipchat had been around since 2010), Slack quickly gained traction, with 8,000 signups on its first day and 15,000 by the second week. Slack’s growth was rapid, reaching $100 million in ARR faster than almost any other company. Its success was driven by a bottom-up distribution model that appealed to both startups and large enterprises—by the time of its IPO, about two-thirds of the Fortune 100 were using Slack.

On June 20, 2019, Slack went public via a direct listing, trading at $38.50 per share and giving it a valuation of around $23 billion—an impressive 57.5x revenue multiple on $400.6 million in revenue (up 82% year-over-year). By that time, Slack had over 10 million daily active users and 600,000 organizations on its platform, with 88,000 paying customers. However, its dependence on enterprise customers was growing larger, with 40% of its revenue coming from just 575 large accounts, and Slack’s roadmap shifted to the needs of these customers.

In late 2020, Salesforce announced its acquisition of Slack, finalizing the deal in 2021. Despite economic tailwinds, Slack didn’t benefit as much from the pandemic as anticipated, facing increasing competition from Microsoft Teams. Bundled with Office 365 and integrated into the Microsoft ecosystem, Teams rapidly gained market share, especially among enterprises already using Microsoft products.

Salesforce’s $27.7 billion acquisition of Slack, completed in July 2021, marked one of the largest software deals ever and Salesforce’s biggest acquisition to date. The acquisition, while significant, wasn’t entirely surprising. However, some, including myself, had long considered Google to be the more logical acquirer, given how well Slack could have integrated into Google’s ecosystem.

Slack’s Identity Crisis: Escaping the Commodity Chat Trap

Slack tapped into a vast opportunity, creating a key part of today’s productivity stack, and became one of the first true systems of engagement. Despite this, Slack faced increasing competitive pressures before eventually being acquired by Salesforce. Since then, no challenger has gained significant traction.

A major reason for that lies in the positioning and commoditization of the market.

Slack continues to evolve what it actually is or wants to become. Salesforce’s latest annual report describes Slack in three different ways: an intelligent productivity platform connecting people and business processes (workflow automation direction), a digital headquarters that brings together companies, employees, and stakeholders (remote work direction), and a leading channel-based messaging platform (workplace communication direction).

Most users still see Slack as a workplace chat tool, despite the product marketing team’s apparent desire to shift this perception.

When we started Back in 2018, we predicted that workplace chat would become a commodity. MS Teams was already on the rise, surpassing Slack in daily active users in 2019, backed by Microsoft’s powerful enterprise distribution. Other players, like Mattermost, positioned themselves as secure alternatives for large enterprises, while major platforms like Google and Zoom integrated chat into their ecosystems.

In emerging software categories, competition often helps educate the market and build awareness.

However, in this case, many competitors were platform players with established distribution channels and other revenue streams. They could afford to subsidize their chat products, driving prices down to near zero, as seen with Microsoft Teams. For these players, chat wasn’t a primary revenue line but a tool to increase engagement and stickiness within their broader platforms.

The market also didn’t exhibit a winner-takes-all dynamic.

Mid-market and enterprise companies frequently used multiple chat solutions. Slack claims that 75% of Fortune 100 companies use its product, but based on our experience, this usage can be confined to specific departments like engineering or IT rather than being adopted company-wide. Many large enterprises have Slack and Microsoft Teams coexisting within their organizations.

As the market leaned towards price over experience, Slack struggled to differentiate its product. To avoid a race to the bottom, Slack has tried to reposition itself multiple times, focusing on three key directions, with Workflows looking like the current focus.

Enterprise Search: Slack’s original promise as a ‘Searchable Log of All Conversation and Knowledge’ aimed to position it as a knowledge search tool. However, Slack is not widely recognized for its search capabilities, and pricing the value of knowledge remains challenging.

Remote HQ: During the pandemic’s acceleration of remote work, enterprises needed to quickly embrace new ways of working. Slack was in a natural position to sell this vision, but ultimately struggled to sell through HR. With the peak of remote work behind us, this direction has lost momentum.

Workflows and Productivity: Delivering on this direction with deeper workflow capabilities might help Slack to defend its rather high perceived price through a clearer return on investment from a productivity angle.

Slack’s ongoing challenge is to redefine its place in a market where chat has largely become a commodity. This is equally a challenge for any new competitor aiming to be either better or different (more on that in the next part).

If you’ve discovered any promising contenders in this space that I’ve missed, feel free to share them with me.